Sourdough bread is pan de sal, and once upon a time it was of kingly size, with hard crust cracked on top. Only an alternative to it were the sweeter, softer breads called pan de limon, pan de agua, or pan de leche, all synonyms for the soft bread with the ridge on top, like two halves joined together.

The large, delicious, yellowish soft bread was pan de monja or “nun’s bread,” whose name through the years has evolved into the racier monay. All were good for dunking in chocolate or eating bread into mamon tostado, a sweet toasted bread beloved by chldren. With the addition of margarine and sugar, stale pan Americano was rebaked and became biscocho de caña or “bamboo bread” (perhaps because of its curved back). Biscocho principe, in turn, was nothing but slices of rebaked ensaymada.

The sugar-dusted ensaymada was part of the bakery’s repertoire, as was pianono, a kind of jelly roll. Mamon de papel, little caked baked in cups of colored papel de japon, made an appearance during the fiesta or Christmas. Special mamon epañola had to be ordered; it was yellow with eggs, a moist rectangular loaf that was good enough to give away as a Christmas present.

Food styles change with lifestyles and times, and in the slower, lazier days, the biscuit had a role in Philippine life. It was for people who had the time to nibble and savor it, with a cup of chocolate or coffee as part of the ritual of merienda. Its loss of popularity shows in the diminished number of biscuit jars in today’s bakeries. In the old days in Pagsanjan, there was quite an assortment of the ever present round, powdery galletas, the flaked jacobina, the square galletas patatas with upturned corners, the round aglipay which was brown, flaky and shiny, and the coin-sized, sweet paciencia, the only biscuit named after a virtue. For the kids, there was a cheap rectangular biscuit they called “radio” and a slender twist of a biscuit called “smoking.” which the boys liked to pretend was a cigarette.

In the afternoon, when the peddlers returned with the unsold bread, the recycling continued. Nothing went to waste. Its best re-use was biscocho. Leftover bread also resurrected as bread pudding that could be bought by the slice, spruced up with stripes of cheap icing. The best buy for one’s money was matsakaw, which was an assortment of all sorts of two-day-old breads — diced pan de sal, monay, pan de agua, even bits of ensaymada.

All these were dumped on a large tray, pushed into an oven, and toasted. They reappeared in a kaing, a deep open basket, and sold for five centavos a bag. From there, too, came the breadcrumbs for thickening the litson sauce and for other kitchen uses. Anything still stubbornly unbought was finally converted into vile little pastries with a bright pink or violet filling of mashed crumbs, its last stand and ultimate disguise.

– Excerpt from Phlippine Food & Life by Gilda Cordero-Fernando

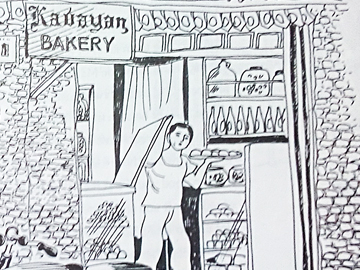

– Drawing by Manuel D. Baldemor